Between Sirens and Silence: Peace in a Time of Fire

In one city, tear gas hangs in the air. Whistles pierce through shouting and sirens—sharp, urgent, relentless. People run, cry, raise their phones to record what’s happening, to document, to bear witness, to make sure the truth is seen. Fear and adrenaline move through the streets. So do grief and rage. The air feels charged, volatile, loud.

In another city, monks in saffron robes move quickly and quietly along a highway on their 2,300-mile Walk for Peace, their steps steady and almost startling in their pace. They walk with purpose, shoulders slightly forward, breath visible in the cold, often with gentle smiles. People line the road there, too. Phones are lifted again—not to capture chaos, but to witness something fragile and rare. Flowers are passed hand to hand. Tears fall. A winter storm gathers in the distance.

Two places. Two movements. The same gestures: watching, recording, trying to hold onto what feels unbearable and meaningful all at once.

Something is tight in the air right now. A kind of collective holding of breath. Anger is rising. Grief is close to the surface. Fear moves through our bodies whether we name it or not. People are watching events unfold and feeling shaken, outraged, protective, exhausted. Some feel betrayed. Some feel threatened. Some feel heartbroken. Some feel furious. And many of us don’t quite know where to put any of it.

The details we see may differ. The interpretations differ. The stories we tell ourselves about what’s happening may be wildly far apart. But beneath all of it, there is a shared human experience unfolding: a sense that the world feels unsteady, and a longing, whether through protest or prayer, to do something in the face of it. A reaching for any way to respond when we can feel how fragile things are, how much is at stake, and how deeply we are searching for something that feels steady, humane, and real.

This moment didn’t begin last week. It has been building. Tension upon tension, grief upon grief, until even ordinary days feel charged. And in the midst of it, many of us are asking the same quiet question, in different ways:

What does it really mean to practice peace

in a world that is hurting?

Peace Doesn’t Mean Passivity

There’s a common misunderstanding that mindfulness, meditation, or inner peace mean staying calm at all costs—not worrying, not reacting, not getting involved.

That is not the peace I practice.

Peace is not indifference.

Peace is not silence in the face of harm.

Peace is not retreating from the world when it becomes uncomfortable.

True peace is presence—the ability to stay awake to what is happening without hardening our hearts or turning away. It is the ground from which meaningful action can arise.

The Courage of Engaged Peace

One of my early entry points into Buddhism was through the writing of Thich Nhat Hanh. He was a Vietnamese monk, poet, and peace activist whose life and teachings offered a way to meet suffering with presence, courage, and deep compassion. He lived through war, displacement, and immense loss. He did not turn away from suffering, and he did not let it harden him. Instead, he showed what it looks like to meet pain with presence.

He believed deeply in what he called Engaged Buddhism—the idea that spiritual practice must respond to the real suffering of the world.

During the Vietnam War, he and his students:

rebuilt bombed villages

provided medical care

helped refugees

advocated publicly for peace

He once said:

“When bombs begin to fall on people,

you cannot stay in the meditation hall all of the time.”

This wasn’t a rejection of meditation. It was an invitation to embody it. Peace, in this tradition, is not withdrawal. It is presence in motion.

Peace is Not the Absence of Anger

Thich Nhat Hanh never taught that anger was wrong or unspiritual. He taught that anger, like all emotions, carries information—and that our task is to meet it with awareness rather than let it consume us.

He wrote:

“Peace is not the absence of war.

Peace is the presence of compassion.”

Compassion allows us to:

grieve when lives are lost

feel anger without becoming cruel

name injustice clearly

act without dehumanizing others

This kind of peace does not make us passive.

It makes us steady.

It allows us to stay engaged without burning out or turning against one another.

Walking as Practice and Prayer

The monks walking for peace right now feel like a living expression of this teaching.

Their walk is not symbolic in an abstract way. It is embodied. It is steady. It is vulnerable. It is happening in real weather, through real towns, amid real fear and division.

Each step says:

We are still here.

We still believe in peace.

We are choosing presence over despair.

What Peace Looks Like Right Now

Peace might look like:

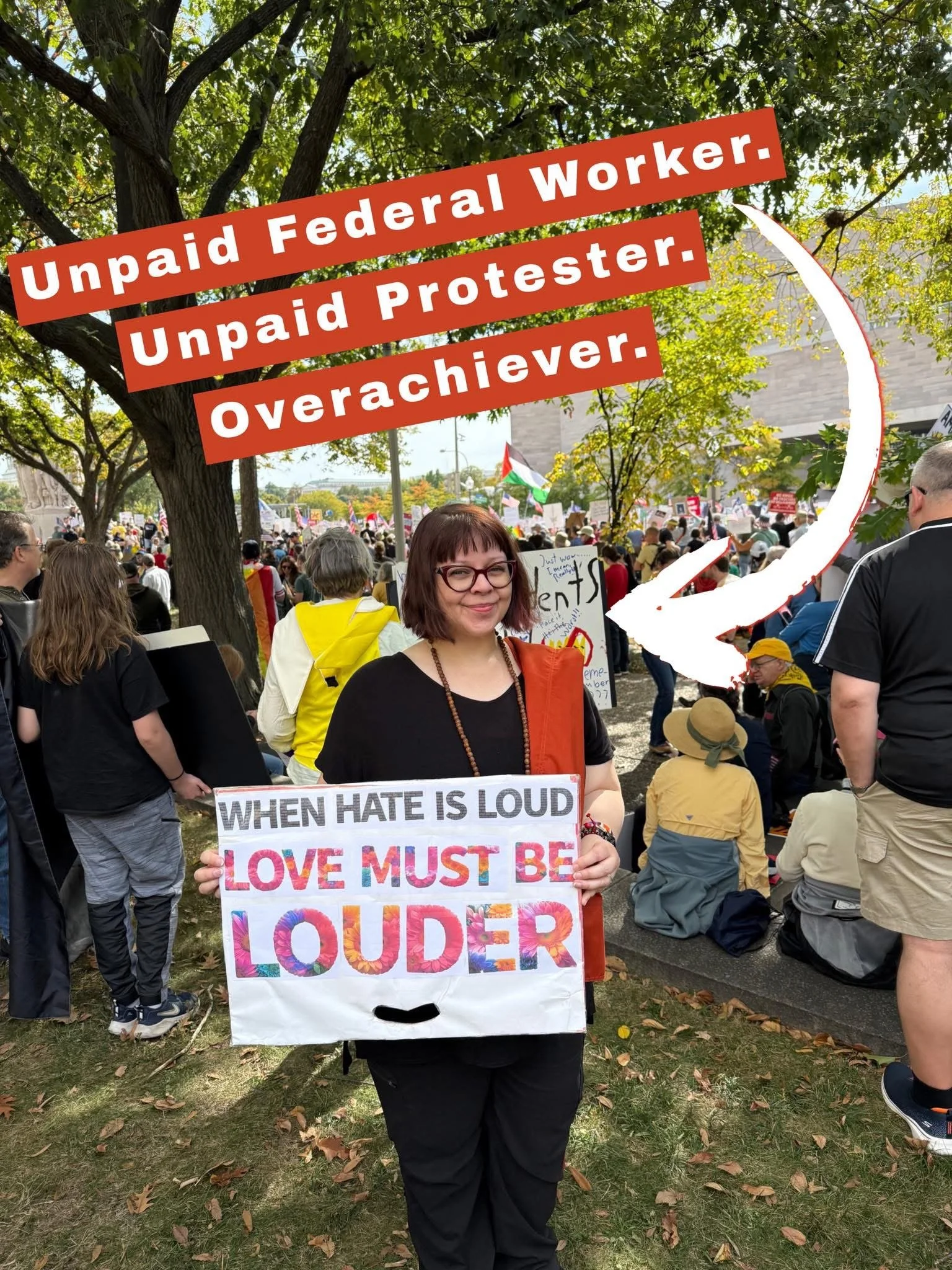

showing up at a protest with grounded intention

supporting neighbors who are afraid or grieving

making phone calls, writing letters, offering aid

having hard conversations with care

tending your nervous system so you don’t shut down

choosing not to dehumanize, even when it’s tempting

Peace is not silence.

Peace is not neutrality.

Peace is not doing nothing.

Peace is acting from love instead of fear—again and again.

Living with an Open Heart in a Broken World

I return to Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings because they remind me that it is possible to live with an open heart in a broken world.

That we don’t have to choose between peace and justice.

That we don’t have to harden ourselves to survive.

That we can walk forward—together—with steadiness, compassion, and courage.

As he once said:

“The next Buddha may take the form of a community.”

A community that refuses to look away.

A community that cares deeply.

A community that keeps walking—through grief, through uncertainty, through bitter cold and long, exhausting days—toward a more peaceful world.

May you and all beings be well and at peace.